Introduction

Reducing stress during livestock handling can increase productivity, maintain or improve meat quality, reduce sickness, and enhance animal welfare. Implementing low-stress handling techniques when working with cattle is the first step to reducing stress.

While temperament in cattle is moderately heritable, environment does play a role and even cattle that are less docile will benefit from low-stress handling methods. A good handler can help reduce fear in an animal, which is the primary driver of negative consequences associated with handling stress. Even if the animal is not experiencing any pain, fear can still cause physical responses in the body, such as high cortisol levels. These responses can ultimately lead to increased susceptibility to illness, lower meat quality, and overall lower performance.

Identifying stress through body language

Cattle in a state of fear or under stress can be identified through their body language. Obvious signs of fear in cattle are running, kicking, vocalizing, and aggressive behaviors towards handlers. Subtle signs of fear are heavy breathing and showing the whites of their eyes. Stressed cattle can cause serious injury to themselves and humans. Relaxed cattle are quiet and walk or trot calmly. When low-stress handling techniques are used, the risk of injury is lowered.

3 Steps for low-stress cattle handling

Besides increasing performance and lowering sickness and injury rates, consumers have indicated that they care that their food is humanely raised. Implementing low-stress handling is a great place to start and comes with many other benefits. Although it may sound like a daunting task, utilizing low-stress handling techniques can be done in smaller steps.

Step 1: Put away the electric prod

Your first step is to put away the electric prod. To decrease use, place electric prods away from where you’re handling cattle but still be accessible in an emergency. This way, instead of instinctively reaching for it, the inconvenience of going to grab it can decrease electric prod use.

Step 2: Understand cattle’s natural instincts

Understand cattle’s natural instincts. We should utilize these instincts to work for us instead of against us. The fact that cattle are prey animals drives a lot of their behaviors. Cattle are herd animals and like to be in groups. When moving them, keeping cattle in small groups (2-5 head) can help keep them calmer and easier to handle.

Additionally, cattle want to see you. Humans are naturally predators and since cattle are prey animals, their instinct is to be able to keep handlers in sight.

Cattle want to go towards lighted areas, and resist going into darker areas. It is easier to see any potential threats in areas that are light. Keep in mind that shadows can reduce cattle flow through an area.

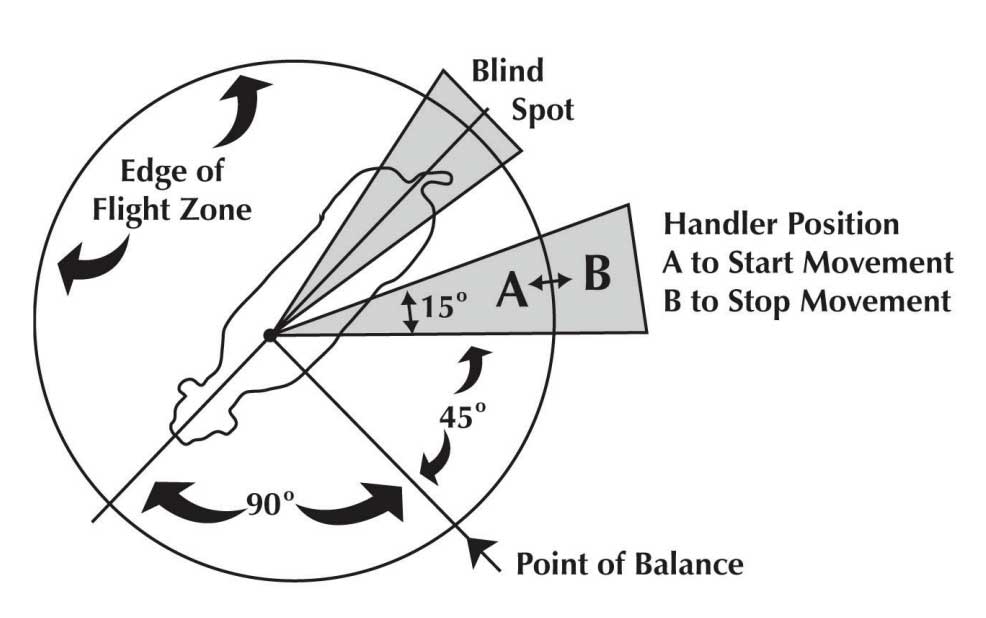

Step 3: Study and use cattle’s natural flight zone

Good handlers study and use cattle’s flight zone and point of balance. These two concepts are illustrated in Figure 1. Walking into the flight zone makes the animal move away from the handler. Stepping out of the flight zone will take pressure off and remove the animal’s desire to continue to move away. Note that the size of flight zones varies between animals. The point of balance allows handlers to move the animal forwards or backwards. Stepping into the flight zone in front of the point of balance will make the animal move backwards. Stepping into the flight zone behind the point of balance will drive the animal forwards. Keep in mind that cattle have a blind spot directly behind them. If you approach the animal in the blind spot, they may get spooked. Walking in a zigzag pattern behind cattle helps let them know you are there.

(Source: Beef Quality Assurance Cattle Care & Handling Guides)

Extra Tip: Taking breaks

Calm cattle are easier to move than stressed cattle. Fearful cattle are more reactive, more easily injured, and more likely to engage in aggressive behaviors. If a handling situation does get intense, take a little break and release pressure on the cattle.

Even taking a brief break can help both the animal and handler calm down and come back to the situation in a more positive light.

Summary

Keep in mind that past negative handling experiences can affect future handling situations, even if the new ones are positive. Over time, implementing low-stress handling techniques while working your cattle can save you time, money, injury, and headaches.

Author

Beth McIlquham

Beth McIlquham is a Regional Livestock Educator serving Crawford, La Crosse, Richland, and Vernon counties. She works alongside producers to provide livestock-related programming aligned with the needs of the area.

References

- Beef Quality Assurance Program. (2019). Cattle care & handling guidelines. https://www.bqa.org/Media/BQA/Docs/cchg2019.pdf

- C. D. Reinhardt, W. D. Busby, L. R. Corah, Relationship of various incoming cattle traits with feedlot performance and carcass traits, Journal of Animal Science, Volume 87, Issue 9, September 2009, Pages 3030–3042, https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2008-1293

- Dewell, R. D., Millman, S. T., Parsons, R. L., Sadler, L. J., Noffsinger, T. H., Busby, W. D., Wang, C., & Dewell, G. A. (2019). Clinical trial to assess the impact of acclimation and low-stress cattle handling on bovine respiratory disease and performance during the feedyard finishing phase. The Bovine Practitioner, 53(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.21423/bovine-vol53no1p71-80

- Petherick, J.C. & Holroyd, R & Doogan, V.J. & Venus, Bronwyn. (2002). Productivity, carcass and meat quality of lot-fed Bos indicus cross steers grouped according to temperament. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture. 42. 10.1071/EA01084.

- Temple Grandin, J.E. Oldfield, L.J. Boyd, Review: Reducing Handling Stress Improves Both Productivity and Welfare, The Professional Animal Scientist, Volume 14, Issue 1,1998, Pages 1-10, ISSN 1080-7446, https://doi.org/10.15232/S1080-7446(15)31783-6.

- Woide, R., T. Grandin, B. Kirch, J. Paterson, “Effects of initial handling practices on behavior and average daily gain of fed steers”, International Journal of Livestock Production, March 2016, Vol 7(3), pp. 12-18, DOI: 10.5897/IJLP2015.0277

Reviewed by:

Bill Halfman, Beef Outreach Specialist

Ryan Sterry, Regional Livestock Educator for Chippewa, Dunn, and Eau Claire counties

Adam Hartfiel, Regional Livestock Educator for Adams, Green Lake, and Waushara counties

Resources for Handling Down Cattle

Resources for Handling Down Cattle Cattle Handling and Stockmanship Influence on Animal Performance

Cattle Handling and Stockmanship Influence on Animal Performance Keep Cattle Cool and Comfortable in Summer

Keep Cattle Cool and Comfortable in Summer Managing and Preventing Pinkeye

Managing and Preventing Pinkeye