Article Series

To understand our poultry industry today, we need to look at the history of the poultry industry.

In times gone by, chickens were kept as a side-line to other farming enterprises. The emphasis in chicken production was on egg production. Standard bred and land races of chickens met the need for white or brown colored eggs. Meat was a by-product, provided when the layer’s egg production diminished or by low value young cockerels that were raised with the high value replacement pullets. “Dual purpose” standard-bred American or English breeds had little significance on meat production. Even caponized (castrated) Asiatic breed cockerels were only noteworthy as a specialty meal. Typically, a 16 week old broiler would weigh 2.5-4 pounds. Many county fair premium books still reflect this type of meat bird.

The seeds of change were sown in the 1920s and 1930s when specialized egg farms began to expand in New England and the Midwest. A few specialized broiler operations appeared in the Delmarva (Delaware, Maryland and Virginia) region, but not enough to make a significant difference in supply of chicken meat.

The return of the GI’s following World War II brought about major changes in American society. America was exporting beef and pork too war-torn Europe and the “Baby Boom” created a high demand for inexpensive protein. This created the urgency for the poultry industry to develop a fast-growing and efficient meat type chicken.

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (or commonly known as the A&P store), the country’s largest poultry retailer, was first to recognize this need. In 1945, in partnership with USDA and Cooperative Extension, A&P set about producing a chicken that would grow bigger, faster and have a larger percentage of breast meat and plump legs and thighs.

A competitive event, called “The Chicken of Tomorrow” was launched that year to find the farmer/producer that could develop the genetics to meet the needs of the consumer. A&P offered $10,000 in prize money nationwide to encourage participation.

The committee used the same principles set down by the 18th century English scientific farmer, Sir Robert Bakewell: Written standards and score cards, models of the ideal carcass and evaluation of large numbers of animals. These principles led to the establishment of purebred associations such as the American Poultry Association in 1874.

In the mid-eighteen century, Robert Bakewell of Dishley, England developed a system that revolutionized animal breeding. His work led to the development of the Leicestershire sheep, Shire horse, Small White pig, English Longhorn cattle and by direct association, the Shorthorn cattle.

Bakewell’s breeding system included three factors: 1) the establishment of specific and written goals and outcomes, 2) breeding only the best to the best, and 3) proving the genetic characteristics of sires by leasing them out to other farmers and evaluating the resulting offspring.

The goals that he established are the Standard of Perfection that we use to evaluate purebred poultry today. His sketches describing the most desirable characteristics that he strove to achieve. The skeletons of livestock that lined the halls of his home provided physical references, much like the models do today.

Refusing to keep any animal that did not meet his strict standards for his breeding program was unique in Bakewell’s day. Only the most desirable animals were bred together, in order to produce the highest quality offspring.

Finally, he proved the genetic superiority of his sires by breeding them to a large number of animals in many herds. Bakewell then assessed the genetic advancements of the offspring.

In 1946 and 1947, a series of state and regional “Chicken of Tomorrow” contests were held. Chicken farmers and breeders from across the country took part in the contest. They submitted 720 eggs for hatching at specially built facilities where the chicks were hatched and raised in controlled conditions on a standard diet. The chicks were closely tracked and monitored for weight gain, health and appearance. After 12 weeks, the birds were slaughtered weighed and judged according to the standard scorecard.

From the state and regional winners 40 finalists were chosen to compete for the national title of Chicken of Tomorrow. The national winner for carcass characteristics was Arbor Acres owned by Henry Saglio, Glastonbury, Connecticut. The White Plymouth Rocks’ white colored feathers gave them the edge.

The Red Cornish crossed with New Hampshire Reds submitted by Vantress Hatchery, Charles and Kenneth Vantress, Marysville, California, won the economy of production for feed efficiency, live weight.

Ultimately, the two lines were crossed, giving us the red-shouldered, pea combed Cornish Rock Cross meat chicken. Today’s broilers are white and single-combed hybrids.

“The Chicken of Tomorrow” contest not only gave us the chicken of today but also the specialized poultry genetics sources that dominate the poultry industry. Arbor Acres® along with Indian River®, Peterson® and Ross® are brand names of Aviagen Broiler Breeders, suppler of day-old grandparent and parent stock chicks to customers in 130 countries worldwide. Cobb-Vantress is a global company using innovative research and technology to make protein available, healthy and affordable worldwide through the development, production and consistency of our high-quality broiler breeding stock.

Henry Saglio and his son, Robert, started Avian Farms International, a broiler and roaster breeding business. At the age of 87, the elder Saglio also founded Pureline Genetics after concerns were raised about chickens bred with antibiotics.

Henry Saglio and his son, Robert, started Avian Farms International, a broiler and roaster breeding business. At the age of 87, the elder Saglio also founded Pureline Genetics after concerns were raised about chickens bred with antibiotics.

Today, Cobb-Vantress Inc. is owned by Tyson Foods, headquartered in Arkansas, the site of the 1951 “Chicken of Tomorrow Contest.”

“The Chicken of Tomorrow” contest, like the advancements in hybrid egg production hens, fractured the poultry industry from centuries of purebred breeding. Scientific principles of genetics replaced the art and eye of the purebred poultry producer.

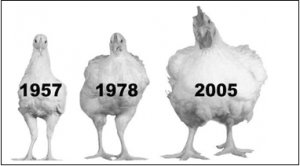

Winners of the contest were lauded for producing a four pound broiler in 12 weeks with 12 pounds of feed. With controlled environment housing, prescription rations and careful bio security, the chicken of today touts a five pound broiler in about 42 days with less than 10 pounds of feed!

Today the average American eats around 70 pounds of chicken a year, five times the 1950 amount. At any given time, 20 billion chickens (That’s three for every human!) are alive on our planet and nearly all of them can trace their ancestry back to Vantress or Arbor Acres stock!

Don't cook your eggs before they're laid

Don't cook your eggs before they're laid Preparing for Winter

Preparing for Winter Avian Influenza and Biosecurity – 2020

Avian Influenza and Biosecurity – 2020